In the shifting and tumultuous political climate, witchcraft has become a source of power and stability for more than 13,000 activists.

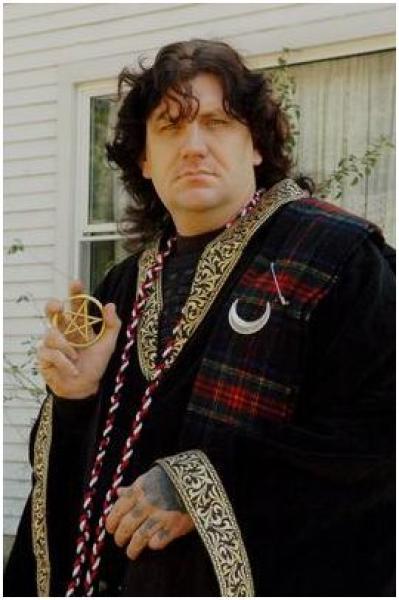

Rapid Cabot Freeman is famous across the Pagan Internet communities for his inflammatory rhetoric. He dotes long hair, facial tattoos, and an unshakeable dedication to the alt-right movement. Freeman whole-heartedly believes in Trump as the leader of the United States. He calls the president amazing and says Trump knows exactly how to handle situations where livelihoods are at stake. In accordance with a majority of the president’s supporters, he loves the way Trump talks like a “regular guy.” But with all his respect for the alt-right, comes his disdain and disappointment for the political left and the people who are using their Pagan beliefs to promote it.

“Ninety percent of the people who claim the mantle of Pagan or heathen have no right to it. When I got into it I was a 16-year-old kid; the movie The Craft hadn’t come out yet and the only place you’d seen a pentacle was on a Mötley Crüe video,” says Freeman, a Pagan high priest based in Connecticut. “And it wasn’t considered a great thing. But I had issues with Christianity and it’s the same issues that I’m having right now with Paganism on the other end of the spectrum.”

This was how Freeman began to wrap up our conversation when I called him on the evening of his 46th birthday. I asked him if another night would work better, but he messaged me back saying “LOL Its My Birthday But For The Alt Right Pagan Movement OK.” His dedication to what he believes in is not up for question. Freeman runs the “American Pagans for Trump” Facebook page, an online community for conservative Pagans to discuss political, cultural, and personal issues.

Freeman is just one member of the small Pagan community that makes up 1.5 percent of the American population that identify with “other religions.” These “other religions” are sparsely populated making reliable estimates of how many Pagans actually live in the United States difficult to track down. Regardless, the other major religious affiliations dwarf the Pagan community. In 2014, over 70 percent of American identified as Christians and 16.1 percent identified as “unaffiliated.” But interest in Paganism and witchcraft has been on the rise in social media and in politics. In 2013, the Public Policy Polling Firm found that Americans preferred witches to Congress at a 46 percent to 32 percent approval rating. The hashtag “#witch” on Instagram spits back over 4.5 million results, and Tumblr houses a dedicated community of blogs that curate “witch vibes.” There is a newfound interest in what happens behind the Pagan broom closet doors.

And this niche, spiritual community established a stronger voice with 2016 presidental election. On Facebook, there are pages of Pagan groups dedicated to discussing politics, “Pagan Liberal” garners 31,000 likes, and even the “Conservative Pagan” page has 740 likes. Freeman’s page “American Pagans for Trump” clocks in at just under 500 likes. And every month under the waning crescent moon, over 13,000 activists participate in a binding spell on Donald Trump.

The spell is part of the larger “#magicalresistance” movement and is one of the largest public displays of witchcraft in recent history catalyzed by President Donald Trump’s inauguration on January 20, 2017. Initially, the movement began as a single spell to prevent Trump from causing harm to be performed on February 24, 2017. Michael Hughes, a Baltimore-based eclectic magician and author who prescribes to a number of Pagan paths, wrote the spell and posted it Medium, Twitter and Facebook. Hughes is a self-proclaimed history nerd. He can walk you through the spiritual history of nearly any Pagan religion He rattles off terms like Greek papyri, santeria, Ifa, traditions you have never heard before. Now 50-years-old, he began studying Pagan traditions in his late teens and early twenties. And because of his encyclopedic knowledge, the binding spell originates from a number of Pagan practices. Hughes optimized the magical qualities to make the spell as effective as possible “I started putting a spell together and I tried to make it kind of generic” says Hughes. “And I tried to make it so it was malleable and adjustable, but still had the core elements of a spell.”

The original spell transformed into a monthly effort to slowly weaken the legitimacy of the president. Within hours of positing the spell went viral and Hughes phone rang off the hook for three full days with reporters looking to get a sound bite from the magic man who was putting spells on Trump. “I think it really hit a need in a lot of people and just so many people embraced from so many different traditions that it was shocking,” he says. “It made me realize there was a really deep need for people to kind of combine their spiritual beliefs with spiritual activism.

Hughes wanted to show that spirituality doesn’t need to be divided between faiths, especially when coming together for a common cause. “We’re all doing magic in different ways, the Christians are doing prayers, the Wiccans might use a spell, but it’s really the same thing,” he says “And for me that’s what this spell getting so big has done, just shown the commonality in spiritual traditions.” Now, ten months out from the original spell, Hughes’s post on Medium attracted more than 1 million views and the “Bind Trump (Official)” Facebook group has more than 3,000 members. The growing numbers prove that this witch-y behavior is trending. Even celebrities like Lana Del Rey participate monthly. Hughes doesn’t mind appropriation of his spell by non-Pagan participants, “I’m all for openness and synergy between different spiritual beliefs and practices. There’s a lot of discussion of appropriation and I take that seriously, but appropriation has always been a part of human culture and society.” And Hughes is on to something. At Syracuse University, Peter Marshall Townsend, an anthropology professor who teaches a course on magic and religion believes that this magical uprising is cyclical and even predictable. “People reach for the supernatural, when the stakes are high, when something is at risk, and when they cannot control advancements through technological means. If they can completely control something then who needs magic, right?” says Townsend. “But if you can’t control certain things and the more important it is, such as life or death or illness, than you find more supernatural.” But Pagan purists, like Freeman, have their concerns.

“They are idiots. They are anti-free will, which is against the beliefs of the faith. I think it’s anti-American. They are hoping the pilot (Trump), of the plane (America), crashes and we are all on board — that is beyond stupid,” says Freeman. “Most of these people are the pop culture-wannabe occultists that use the faith for attention. They don’t live the life 24 by seven by 365 like my people and the nationalist minded occultist that really live this life, [that] I call my friends.” Raised in a house divided by his Cherokee father’s shamanic traditions and his grandparents’ German Methodists beliefs, Freeman’s formative years developed around the Pagan traditions found in both these practices. He believes in the legitimacy of his claim to the Pagan title. Now, as a third-degree high priest he formed his own faction of Paganism, the Firstblood Tradition. Based on Kent traditions found in English Wicca combined with Pagan native folk traditions, the Firstbloods believe that if you are steadfast in your beliefs, the old ways and the old gods then you are considered a brother. The coven came to fruition in 2009. As of 2017, its members stretch across the Atlantic with offshoots in Germany and Scotland.

As Freeman tells me about his religious beliefs and his coven, he interjects with snippets about his political persuasion as well. He tells me how he thinks Tammy Lahren is great, shares his thoughts on Muslims (pronounced with a long u sound — “Moo-slims”), and how he doesn’t allow anti-American sentiment at events he sponsors. He sides with the Democratic or liberal views on some key issues: marriage equality and women’s rights, for example. “It’s not really my religion per say that’s supporting my political views, it’s the moral compass that I got from [my religion] supporting my political views. I want everybody to be safe,” says Freeman. “I want everyone to raise their children and not have anyone tell you where to sleep or how to eat, you know? But despite being a minority in the Pagan community with his controversial opinions and beliefs as a Trump supporter, Freeman isn’t the only member with concerns over the trendy spell.

In North Carolina, a British expat, Elizabeth Watkins lives in Asheville, a city of 89,000 citizens. Watkins claims Asheville is quite liberal despite its location in the middle of the Bible Belt. Watkins is middle-aged with mid-length brown hair and round wire frame glasses. She is married and raising a three-year-old daughter, who she refers to as “her little witch.” Like Freeman, Watkins is a bit of a political hummingbird. She flits from issue to issue as she sees fit. However, she is his exact antithesis. She felt disappointed when the marriage quality movement died down, so now she seeks to satiate her urge for social justice in Black Lives Matter and trans rights groups.

But in accordance with Freeman, Watkins doesn’t agree with the binding spells being performed each month. “I am not a fan of Donald Trump, obviously. But he is not the only person doing this shit,” she says. “By hexing him are you really fixing anything? I don’t think so.” Instead, Watkins she focuses on inclusive rhetoric and social change, not spells. In November 2016, she formed her own coven, Open Coven, following the presidential election. It began as a blog that aggregated occult content from female, LGBTQ+, and other marginalized artists. She saw an opportunity to turn the blog into a motivator for change and morphed her mission into developing a spiritual community around liberal issues. Strictly for women, Watkins is hoping to promote a strong feminist agenda via Open Coven. Though it is small, with only three members, there are plans to create a larger movement and connect with other liberal-minded fringe groups across the nation.

The truth is both Freeman and Watkins working towards their version of a bright American future. Watkins wants a network of liberated Pagans to collaborate on art, protests and creating a more feminist future. And the future Freeman wants is a return to the way he believes America used to be. He reminisces about Blazing Saddles, calls himself “kraut” for his German heritage, and discusses how believes stereotypes hold some truth. “Everybody got along then because we could laugh at each other. It wasn’t a big deal,” he says. “And now it’s gotten to the point where everybody is nuts.”

Before we hang up, Freeman tells me about Tony, one of his best friends who passed away. Tony was a Vatican knight and worked in the same building where Freeman ran his own cable access show. The pair would get coffee together every day. “We both believed in a god, we both believed in our country, we both loved our kids. We would both go to the fire department breakfast, ya know? American.”

- Log in to post comments